It is just possible that the extinct ancient spice known as silphium, (also known as sirpe, silphion, laserwort, or laserpicium), so valued by the Greeks and Romans for its medicinal and culinary properties, has been rediscovered. It’s quite an appealing idea, but also very difficult to prove. We have so little solid information about what Silphium tasted like. No ancient author describes the flavour at all, only acknowledging that it smells better than the Median kind, asafoetida, and we know that one stinks to high heaven so it’s not a lot to go on! It must have tasted pretty special to have acquired such a reputation but it may not be that simple. In this post I am going to lead you through the culinary journey we are taking (and still taking) to understanding this discovery and the experiments we engaged in to judge the properties of this newly rediscovered spice in Roman food. It is clear that the medicinal qualities of these resins were paramount to the ancients and it will be through medical advances that this resin will be most beneficial. It is not entirely certain how much true culinary value we can attribute to this plant today.

‘Laser, a juice which distils from silphium, as we have already stated, and reckoned among the most precious gifts presented to us by Nature, is made use of in numerous medicinal preparations.’ Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis Historia 22.101.1

Silphium 101

But first we should deal with the basics of silphium. If you are here you probably know quite a bit about the spice already, so I’ll try not to be too longwinded! There are many sites that provide all the material and detailed descriptions. If you are still fond of real books the basics can be found in Andrew Dalby’s Food in the Ancient World: From A to Z (2003:303) The wiki page is extensive and more than adequate: Silphium – Wikipedia. The plant is understood to be a member of the ferula species which includes 190 plants that provide many valuable resins and thus spices, including asafoetida, (ferula asafoetida) – also known as ‘devil’s dung’ or hing – which of course replaced silphium when it became extinct, and various other species, particularly sagapenum (ferula Persica and ferula szowitziana), a plant that currently provide resins that are used to adulterate asafoetida. Sagapenum generates less sulphurous resins and so one might say that adulteration is the wrong term, as the blending process may actually tone down the devil in the hing. One of the pleasant resins, Galbanum (ferula gummosa), provides a resin which is one of the most valued in the perfume industry. Most if not all ferula species seem to provide a form of resin, and it is their perfume that is most valued today. The aroma can be delightful or repulsive or neither, while the taste of many of these resins is bitter and disagreeable. They are not natural culinary spices, and that is the crucial question we have to contend with. Did silphium actually taste good or did it smell so good that the natural bitterness was tolerated? Our first experiments certainly suggest this may be the secret to silphium resin. The smell of the fresh resin was delightfully fresh and green – floral, in fact – similar to galbanum and, and when burnt also reminiscent of frankincense. When we were able to taste that smell without bitterness it proved to be very appealing but also elusive. It was also easily destroyed by heat and time as well as hidden by the complex flavours of many Roman recipes.

‘The Cyrenaic, even if one just tastes it, at once arouses a humour throughout the body and has a very healthy aroma, so that it is not noticed on the breath, or only a little; but the Median and Syrian are weaker in power and have a nastier smell.’ Dioscorides, Materia Medica 17.3.22 (about AD 50).

The Syrian and Median mentioned here along with the more familiar Parthian varieties are, as we can guess, forms of ferula species that generate sulphurous resins that were collectively known as ‘silphium’ too, after the extinction event, and these are known to us as asafoetida. This generalisation of terms makes precise identification challenging. As the recipes we rely on are largely in Apicius and the date of this text is obscure, we cannot know to what extent cooks expected all or most the recipes to be made with asafoetida, because silphium itself had long since died out completely. A rare recipe states ‘Laser sauce: you dissolve Cyrenaican or Parthian laser in warm water blended with vinegar and liquamen‘ (1.30) This probably implies a very old recipe rather then access to silphium in the 4/5th century, the purported date of the finalised recipe collection.

‘For a long time now the only laser brought to us has been that originating in Persis, Media and Armenia, plentiful but much inferior to Cyrenaic and moreover adulterated with gum or sacopenium or bean-meal’ Pliny The elder HN 5 33

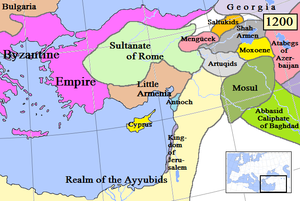

The claim that silphium had been found came from Prof Mahmut Miski, a pharmacologist whom I have subsequently met and worked with on this project. He is a professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy, Istanbul University , where his role is to discover new drugs, and the ferula species was his special area of study. I made contact after reading about his early research back in 2018. Mahmut had found a ferula species called Drudeana growing in plain sight in the Anatolian mountains of south eastern Turkey. Mahmut considered it significant that it was an area that claims hereditary links with the Sultanate of Rum, largely populated by conquered Byzantine Christians who still considered themselves Byzantine ‘Romans.’ Stories from the late empire in the 5th century AD had suggested that plants had been transplanted successfully to Turkey, though these had never been taken seriously. ‘Synesius, a Cyrenian aristocrat and bishop of Ptolemais, claimed that he had seen the plant itself and sent lots of silphion juice to his friend Tryphon in Constantinople’ (Miski 2021: note 19). The assumption should be that this was the second rate silphium i.e. asafoetida, as there is rarely any distinction made in the use of the term.

Terminology is always key and sadly there is little clarity. to it Silphion is the normal Greek term for the plant, while the resin is referred to as sirpe and laserpicium or laser in Latin and opos or just silphion in Greek. The early Greek sources make far more use of the whole plant. The stalks, kauloi, were both boiled and baked, and Aristophanes tells us that sailors who consumed this would characteristically break wind on their fellow rowers afterwards. We know that in the 5th century BC Cyrene specifically exported silphium stems, while the trade in the juice (i.e. resin), though probably included, is unmentioned. The leaf, maspeton, and the root were also consumed widely and were apparently pounded in a mortar into sauces. ‘There are two kinds of opos, ‘juice’, one from the stem, one from the root, hence called kaulias and rizias‘ (Theophrastus 6.3: Athens 310 BC).

(Miski 2021 figure 2)

Ferula Drudeana resembled silphium in many respects: it looks exactly like the illustration on coins, its seeds and leaf are the same, and the root fits the description in Theophrastus. The plant’s lifecycle fits the description, the resin appears to be harvestable in the same way ,and the resin has the potential to be delightful.

For Mahmut, the conviction that the ancient medicinal properties of silphium were potentially present in the resin of the plant that he had discovered was the root of his suspicion that this was actually silphium. Initially for him the culinary aspect were secondary to the potential for drugs. There have been dissenters of course, fellow scientists who dismiss Mahmut’s claims. Time will tell, as it will be a long and complicated process to judge this new species. Read Mahmut’s article below!!

Tasting silphium in Istanbul

Our first meeting took place in the spring of 2022 when we all – that is, Mahmut Miski, Taras Grescoe, a food writer who had become just as absorbed and fascinated by the discovery, and myself – met up in the Botanical Gardens of Istanbul.. Check out Taras’ new book which includes a chapter on our journey to discover silphium: The lost supper: searching for the future of food in the flavours of the past:

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/taras-grescoe/the-lost-supper-future-food/

The plan was to cook with the first harvest of the resin and also with the root, as many recipes appear to want that rather then the resin. It is very likely that those recipes in Apicius that use the root will actually mean the root of asafoetida rather than silphium. There is currently no trade in asafoetida root, and despite endless attempts to communicate with growers and traders I have failed to make contact with anyone who could help me with this. There is a hint that a cheap and rarely-traded powdered asafoetida available in India is actually made from the ground up thin root slices that are cut in order to stimulate the flow of resin. My attempts to buy this are ongoing. If by any chance someone reading this can help, please please get in touch! I expect that the root would be relatively weak in the sulphur flavour found in the asafoetida resin.

The first harvest of resin in the spring was fresh but tiny – a miniscule amount in fact – as we had failed to consider that the resin should be taken after the summer’s heat. With hindsight it was more flavourful than the resin that I was subsequently sent after being in storage for 6 months. Even so it was quite subtle. I chose numerous dishes including a lamb tagine with dried plums (8.4.1), a laseratum (1.30) – a simple sauce, roasted quail (Vinidarius xxx), a Alexandrian style goude (3.4.2.). I don’t have recipes to share yet but will do shortly as a new book is forthcoming. We discovered that roasting destroys the flavour, unlike asafoetida which improves considerable after a good roasting! We found that the best option was the lamb with fruit, as this brought out the floral notes. The simple laseratum gave the best clean flavour, which was appealing , there is a delicate flowery scent which reaches the taste buds as some thing similar to artichoke and it was very green. We were excited and felt we had achieved something even if it was rather less than the great revelation that we wanted.

Silphium tasting #2

6 months later and a substantial amount of the resin became available after a summer to cook the roots in the ground and mature the plant. However Mahmut was unable to send it to me directly as the whole thing had become rather politically sensitive. It sat in storage for at least 6 months before we could meet up and exchange samples. The detailed description of the harvesting process from Theophrastus is as follows:

The root has a black skin which they strip off. Its collectors cut in accordance with a sort of mining-concession, a ration that they may take based on what has been cut and what remains, and it is not permitted to cut at random; nor indeed to cut more than the ration, because any surplus spoils and decays with age. Exporting it to Piraeus they prepare it as follows: after putting it in jars and mixing flour with it they shake it for a long time — this is where its colour comes from; and thus treated it remains stable.

The team who collected the root for us could not do this, and it was not possible to do it subsequently . We are not sure what Theophrastus means by the term ‘spoils and decays in terms of the flavour,’ but as you will see the flavour was difficult to discern the 2nd time, and even more so than in the experiments in Turkey. The bitterness was most apparent in every dish as if the time and in fact the heat had destroyed the flavour.

It arrived here in my Hampshire home in the spring of ’23 and it stayed tucked away in a cupboard for some time, as I was unsure, nervous and apprehensive about testing it again, and I was right to be so as you will see when you watch the film. I wanted to make an event of the tasting and that, I think was an error. I invited guests from around the world and made much of the event. I cooked the same dishes as in Istanbul and as I was expecting 8-10 people I did much of the preparation in advance so that I could play mine hostess. Ha Ha ! I won’t do that again. It was very apparent that time in every respect had altered the flavour. The time spent in storage in Turkey, the time spent at my house and the time spent blended in the pre-prepped food had almost destroyed that delicate flavour we had hoped for. All that many of us could detect was bitterness. It was also clear that heat, cooking heat, interfered with the delicate balance. I found that some sauces when I made them tasted fine, but subsequently when gently reheated gave nothing in the way of flavour. Fresh resin freshly blended or stabilised as described in Theophrastus would seem to be the best option, and when this is achievable I think we could then begin to see that something as wonderful as we expect and want silphium to be has been found.

Now and only now will I post the You Tube film so you can watch our guests at the tastings.

Every best wish to all of you and thank you for your continued interest and support!

Sally Grainger